Stay Informed

Follow us on social media accounts to stay up to date with REHVA actualities

|

|

Caroline Milne | Maria Stambler |

Head of Communications, BPIE (Buildings Performance Institute Europe) | Communications Manager, BPIE |

Buildings are responsible for 36% of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in the EU; reaching our climate targets requires a clear roadmap to decarbonising our living and working spaces. Currently, the EU is aiming to be climate-neutral by 2050. The European Commission proposed to raise the EU 2030 climate target from 40% to at least 55% below 1990 levels, an ambition which has been discussed and is now endorsed by the European Parliament and the Council. And with the ‘Renovation Wave’ Strategy, the Commission aims to double annual energy renovation rates in the next ten years.

Beyond climate goals, the pandemic and resulting economic crisis has recently brought EU buildings into sharper focus: renovation offers a unique opportunity to rethink, redesign and modernise our buildings and homes, and to boost renewables supply to make them fit for a greener and digital society, better prepare them for future climate impacts and sustain the economic recovery. Within this context, ambitious national Long-term renovation strategies are foundational to achieving not only climate goals, but also sustainable economic recovery and smart, efficient spending of EU recovery funds.

The Energy Performance of Buildings Directive 2010/31/EU (EPBD), amended in 2018, together with the Energy Efficiency Directive 2012/27/EU (EED), is meant to trigger policies in the EU-27 towards achieving a highly energy efficient and decarbonised building stock by 2050, while providing a stable environment for investment decisions and enabling consumers and businesses to make more informed choices to save energy and money.

A key pillar of the EPBD are national Long-term renovation strategies (LTRS), which should enable implementation of these efforts on the ground through strategic planning, effective policies and financial support at Member State level.

As prescribed in the EPBD, Member States are required to (within their LTRS) develop and measure progress, provide indicative milestones for 2030, 2040, and 2050, as well as estimate the expected energy savings and wider benefits, and the contribution of building renovation to the Union’s energy efficiency target. It is also an important input to the “Renovation Wave” -strategy [1] for buildings, announced as part of the European Green Deal.

According to the European Commission, national Long-term renovation strategies must include:

· an overview of the national building stock;

· policies and actions to stimulate cost-effective deep renovation of buildings;

· policies and actions to target the worst performing buildings, split-incentive dilemmas, market failures, energy poverty and public buildings;

· an overview of national initiatives to promote smart technologies and skills and education in the construction and energy efficiency sectors.

The strategies must also include a roadmap with:

· measures and measurable progress indicators;

· indicative milestones for 2030, 2040 and 2050;

· an estimate of the expected energy savings and wider benefits and the contribution of the renovation of buildings to the Union's energy efficiency target.

On March 10, 2020, EU Member States were expected to submit their third LTRS, in line with requirements of the EPBD.

By September of the same year, BPIE found that less than half of Member States’ strategies had been submitted [2] and of those, few were compliant with EU legislation. Now approaching the middle of 2021, well over a year since the submission deadline, a small number of national strategies are still missing. Late submission appears a symptom of a broader malaise when it comes to prioritising the building stock. BPIE’s most recent analysis of 2020 strategies [3] shows that the majority of submitted LTRS are not in full compliance with the EPBD objective of achieving a highly efficient and decarbonised building stock by 2050.

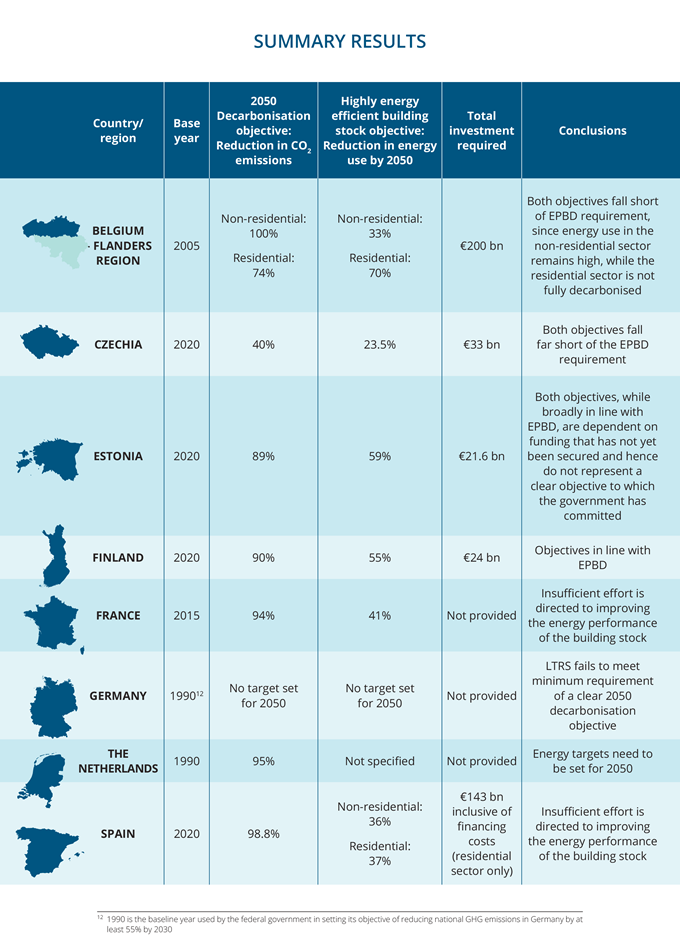

The analysis, representing over 50% of the EU population (covering seven EU Member States and one region, Flanders, Belgium), shows that the majority of Member States fail to provide sufficient detail over the entire period to 2050, to enable an evaluation of whether the supporting policies and financial arrangements are adequate to meet the goals. Most strategies appear to put more effort towards decarbonising energy supply systems and greenhouse gas emissions reduction, rather than actively improving the energy performance of buildings, reducing overall the energy consumption in this sector.

Figure 1. Results of BPIE’s analysis [4] of several European LTRS.

Half of the analysed strategies (Spain, Finland, France, and the Netherlands) include an objective at or above 90% GHG emissions reduction, which is in line with the legal requirement of EPBD Article 2a, which requires Member States to set a long-term 2050 goal of reducing GHG emissions in the EU by 80-95% compared to 1990.

However, none of the eight strategies targets 100% decarbonisation of the building stock, which is needed to achieve climate neutrality. This means that the substantial increase in renovation activity that is required – a deep renovation rate of 3% annually by 2030 [5] – is unlikely to be achieved. Given the new political developments since the 2018 EPBD recast, including a strengthened EU 2030 climate target and 2050 climate-neutrality law, it is clear that even strict adherence to the LTRS as defined in the EPBD is now insufficient.

While both decarbonisation and energy efficiency are clearly needed, a greater focus on energy performance would bring with it many economic, environmental and societal benefits, such as improved indoor air quality, better health, job creation and alleviation of energy poverty.

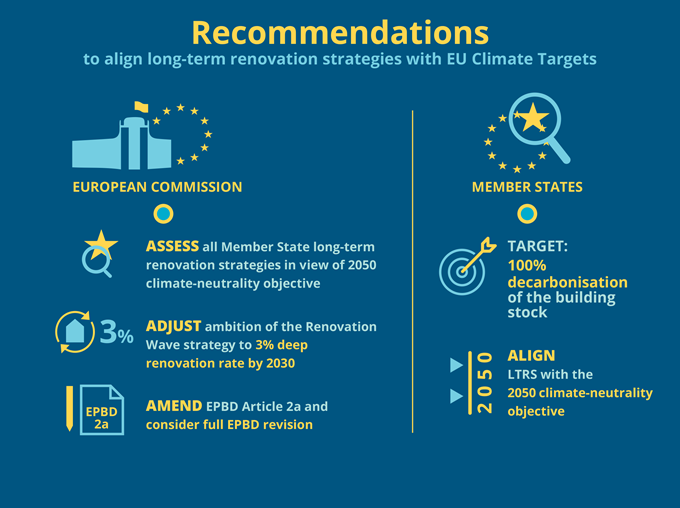

There is now a clear misalignment between LTRS and the EU 2050 Climate targets, which must urgently be addressed. This will require concerted effort from both Member States and the European Commission.

To start, Member States should now seek to increase the ambition of their renovation goals to 100% decarbonisation of the building stock and revise their strategies to ensure effective delivery This could be done through a reworking of their 2020 strategies in the near future, but certainly no later than the deadline for the next iteration, in 2024.

The European Commission, in turn, should use the opportunity of legislative revisions in 2021, to ensure a full revision of the EPBD (and LTRS), in line with the ‘Renovation Wave’ and the new 2030 Climate Target. The 2021 revisions should also ensure an revision of EPBD Article 2a, to require full decarbonisation of the building sector by 2050, with most of the effort to be directed to improving building energy performance and the delivery of a highly energy efficient, nearly zero-energy building stock.

The Commission should furthermore assess all Member State LTRS not only in accordance with the legal text of EPBD Article 2a, but also in view of aligning the full directive with the climate-neutrality objective by 2050 (meaning a higher decarbonisation objective and stronger emphasis on reducing the energy demand in the buildings sector), and guide Member States accordingly for their LTRS update which is due by 2024 at the latest. The ‘Renovation Wave’ ambition should also be adjusted, to deliver a 3% annual deep renovation rate by 2030, the required rate to fully align the buildings sector with the climate-neutrality objective by 2050.

Figure 2. Recommendations to align LTRS with EU climate targets. (Source: BPIE report “The road to climate-neutrality: are long-term renovation strategies fit for 2050?” [6])

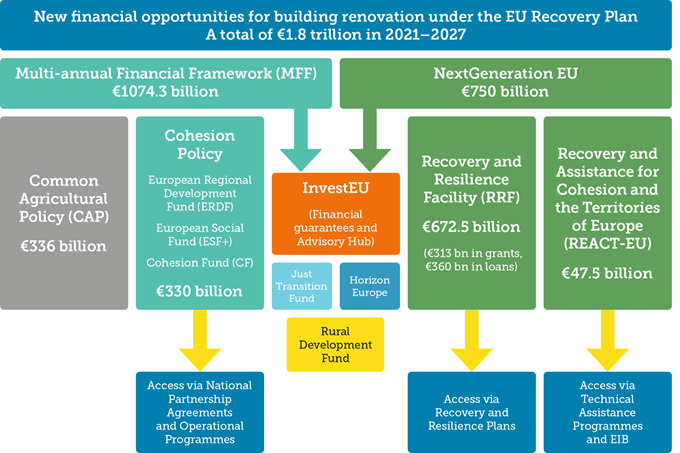

While aligning legislation and strategies with Europe’s climate targets represents a real challenge, we know that the climate won’t wait. We also know that the European Union’s Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) will channel some €672.5 billion in loans and grants to support reforms and public investments undertaken by Member States, and minimum 37% of Member State RRF allocation must go towards climate priorities. Member States therefore have every reason to align their LTRS with the climate-neutrality objective, as this should also guide effective spending of recovery funds to stimulate both short- and long-term economic growth.

The European Commission first proposed the RRF in May 2020, and by September, issued a guidance to Member States on how to draft their Recovery and Resilience Plans (RRP). The guidance identifies seven ‘thematic flagship’ areas suitable for spending the recovery money. ‘Renovate’ is the second flagship mentioned as an area the Commission “strongly encourages” Member States to include as an area to foster economic growth and job creation. The RRF entered into force [7] in February 2021, with end of April 2021 being the deadline for Member States to submit their national Recovery and Resilience Plans (RRPs). At the time of writing in May 2021, almost all RRPs have been submitted, showing that most Member States are largely on track and have been able to respect the deadline.

Figure 3. Overview of the EU Recovery Plan including the MFF 2021–2027 and the NextGeneration EU budget, BPIE’s illustration based on EU Council infographic.

The speed at which Member States have submitted their recovery plans, particularly in comparison to their LTRS, highlights the political – and existential – weight that is, understandably, given to economic recovery. While the pandemic, and the myriad of economic, mental and physical health impacts on Europe’s population have been great, the context of recovery is a game changer – more money is now available for building renovation than over the last five years altogether including Regional and Cohesion Funds.

Member States should therefore not be quick to dismiss improving upon their LTRS (or submitting – for those who are still late). A strong and ambitious national renovation strategy is the key to impactful spending. The recovery money, in turn, offers an unparalleled opportunity to implement the Renovation Wave on the ground.

[1] The Renovation Wave intends to create the necessary conditions to scale up renovations and reap the significant saving potential of the building sector. (https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/fs_19_6725), https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_20_1835

[2]https://www.bpie.eu/publication/a-review-of-eu-member-states-2020-long-term-renovation-strategies/

[3]https://www.bpie.eu/publication/the-road-to-climate-neutrality-are-national-long-term-renovation-strategies-fit-for-2050/

Follow us on social media accounts to stay up to date with REHVA actualities

0